Don’t Hold Yourself

Back From Growth – External and Internal

By Alan ‘Shlomo’ Veingrad

Reunions -

high school, college, jobs, family - are always times of challenge and stress. Will

I be recognizable? What will people think of me? Will I be embarrassed?

And yet,

it is almost essential to not only be prepared for change that can come with

time, but to seek and embrace it. Whether it involves your business, company,

career or inner-self, standing still, being stagnant, is not the best choice,

in good times or bad.

In my

case, it’s been 20 years since my fast-paced, 6-foot-5 285-pound offensive

lineman days on a Dallas Cowboys team that won Super Bowl XXVII with a roster of

Hall of Fame and NFL No. 1 Draft Pick players, household names like Troy

Aikman, Emmitt Smith and Michael Irvin.

Today,

instead of pointing at opposing lineman or trading barbs, I point out investment

products and provide motivational speeches related to personal transformation.

But what

has changed most is my inner-self through my decision to connect with my roots

-- to become a Torah-observant Jew. Following my pro football career, I traded my

No. 76 jersey for the daily prayer shawl, my helmet for a yarmulke and beard,

by English name for my Hebrew name.

I have

received publicity over the years with my internal transformation. And some of

my fellow teammates were aware of it when I went to Cowboys Stadium on Sept. 23

and attended the 20th anniversary of our Super Bowl winning team.

Still, you never know about a re-union, until you arrive.

“Shlomo!” yelled

out former defensive lineman Russell Maryland, boisterously addressing me by my

Hebrew name when I entered the special suite for the gathering of former

champion players.

Others in

attendance were not familiar with my transformation, or religion, for that

matter, until they saw me wearing a yarmulke.

“I didn’t

know you were Jewish,” said former teammate and defensive end Charles Haley.

“Yeah!” I

responded. “I was then and I am now.”

Half way

through the second quarter, we took an elevator down from the suite for a

special, on-the-field half time ceremony. We gathered with Hall of Fame

quarterback Roger Staubach and other players from the Cowboys’ Super Bowl XII winning

team.

Wrote CBS

sports blogger Richie Whitt after the game: “With 5 Super Bowl banners hanging

from the rafters, the halftime ceremony honoring the title teams of ’77 and ‘92

featured one player (Jethro Pugh) using a walker, and another (Alan Veingrad)

wearing a yarmulke.”

I was

self-conscious that almost 82,000 fans could have been watching me on the

world’s largest HDTV screen high above the field. But I was also proud to have

worn my yarmulke. After the game, obviously more recognizable than before it, I

was enthusiastically approached by fans asking me to sign their Cowboys hats,

programs and other paraphernalia. Later, Jason Garrett, my former teammate and

current Cowboys head coach, warmly greeted me at another

special gathering in the stadium. Garrett was already familiar with my

spiritual growth based on an article he read.

“You are a

legend around here,” he said, as we posed together for a photo. “How’s all that

wisdom?”

For all

the good ribbing and conversation, I was getting hungry for some kosher food,

as was my son, who had joined me on this special journey about my past. But I

certainly left filled intellectually and spiritually from the experience and

knowledge that I gained. The program had reinforced what I often speak about:

Don’t be afraid of change and what other people think of you; People are not

always laughing at you, but with you.

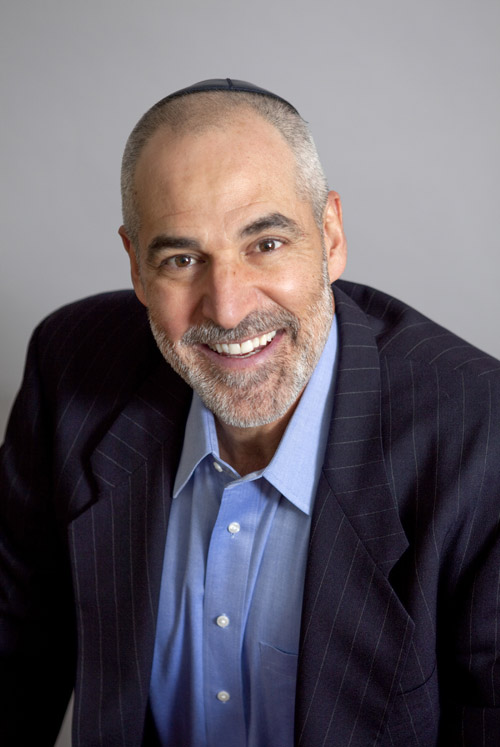

Alan

‘Shlomo’ Veingrad has inspired thousands with his candid, humorous,

inspirational and spell-binding tales on life in the ultra-competitive NFL, and

how he took that fire to transform himself into a Shomer Shabbat and observant

Jew following his playing days. Based in Boca Raton, FL, Veingrad has traveled

from New York to South Africa speaking at camps, Shabbatons, school programs, yeshivas,

scholar-in-residence programs, men’s clubs, as well as charity fund raising

events. He is often asked to speak to businesses and corporations looking to

inspire their employees, and is an inductee of the

National Jewish Sports Hall of Fame and Museum. For speaking engagements,

Veingrad can be reached at alan@alanveingrad.com. To read more and see

videos about him, visit www.alanveingrad.com.