Friday, May 11, 2012

No Quick Fix To NFL Concussion Saga

As a rookie offensive lineman on the Green Bay Packers in 1986, I was awe struck by our coach, Forrest Gregg, a Hall of Fame offensive tackle whom the legendary Vince Lombardi called “the best player I ever coached.”

An imposing figure at 6-foot-4, 250 pounds, Gregg had a commanding presence with his black piercing eyes and deep Texas drawl, a Super Bowl ring dangling from a crooked finger gnarled from professional football’s trenches.“This is a violent game,” Gregg would tell us players.

But there was no additional warning that a career in the National Football League could physically, mentally and financially affect our post playing days.

After seven years, I finished my pro football career with a Super Bowl ring from the 1992 Dallas Cowboys championship season. I walked away from the game – while I could still walk. Unfortunately, the same can not be said for many other NFL players.

Some, financially broke or deeply depressed, have taken their own lives, the most recent being the tragic ending of All Pro linebacker Junior Seau at age 43, in San Diego. His ex-wife said Seau suffered concussions in his long career, and researchers at Boston University have asked to study his brain.

Seau’s death comes on the heels of an assistant New Orleans Saints head coach being caught on video urging his players to injure, for money, opposing players, using shots to the head. The bounty scandal has the league in a public relations scramble, and rightfully so, despite levying heavy suspensions and fines to Saints coaches, management and players.

Health warning labels are placed on products like alcohol and cigarettes. Maybe it is time to put a sticker on player helmets warning of the game’s hazards to health and life.

When I entered the NFL as a 23 year old free agent from East Texas State University (now Texas A&M Commerce), I was 6-foot-5 and 280 pounds. I ran the 40 yard dash in 4.9 seconds and bench pressed 500 pounds. My mind at the time said I was “Superman.” It is hard to know what I might have done if I learned the full risks of playing pro football.

For sure there were moments where I saw black after delivering a block for teammates like Dallas Hall of Famers Troy Aikman and Emmitt Smith. I also suffered “stingers,” a burning, tingling, painful sensation that radiates down your arms when nerves are compressed near the spinal cord. Today, my back has plenty of stiff moments. Other times I suffer an extended dull headache. I am one of hundreds of former players suing the NFL for failing to adequately warn us of dangers they knew or should have known.

I do hope the league has clamped down on prescription drug and alcohol abuses common during my days in Green Bay. Following games, Packer players lined up to see the doctor and received a hand full of pain meds and a sleeping pill the size of a quarter that we called “The Green Bomb.” On charter flights home, players washed pills down with as many as a dozen ice cold beers provided by the flight attendants on the tarmac.

It has been well documented that alcohol and prescription drugs taken together can injure your heart, liver or even kill you. Players addicted to pain pills were forced to enter drug rehabilitation centers -- only to become depressed on becoming clean. Anti-depressants in some cases made them further depressed, leaving them in a deep, dark place.

Besides warning labels on helmets, maybe the league should go retro, replacing hard plastic helmets with padded leather ones, football gear circa 1920. Eliminating face masks might also cut down on jarring hits by players propelling their bodies head first like missiles.

All that seems unlikely.

Pro football is a business. Hard hits sell the NFL, bringing $9.5 billion to the league during the regular season. Seats are filled by plays like a wide receiver being walloped after catching a ball while crossing the field, the quarterback being sacked, or kick off teams unloading high speed blocks on each other. Eliminating thunderous collisions, for fear of brain damaging concussions, would not fill seats. And the NFL wants to sell seats.

So the unanswered question remains, what can the NFL do to keep the game popular, but safe? There appears to be no quick fix to the dilemma.

The NFL should do a better job educating players on dangers of playing the game. It must also continue to lay down severe penalties if players – on their own initiative or at the direction of coaches -- intentionally try to hurt other players.

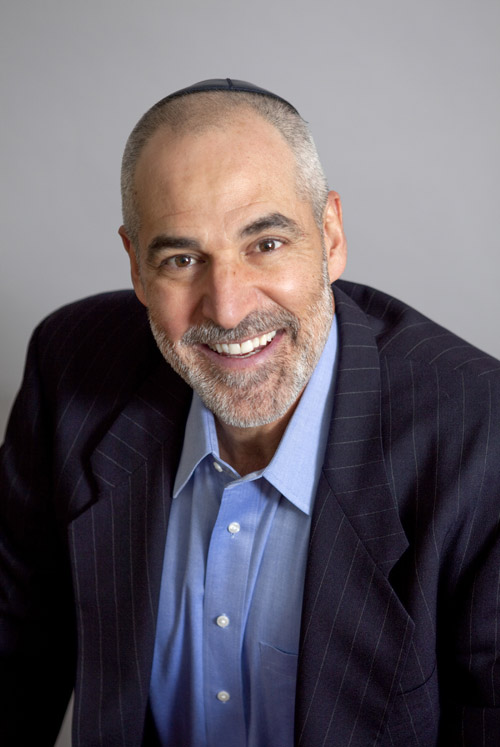

Alan Veingrad was raised in Miami and resides in Boca Raton. Following his professional football career, Veingrad has worked in financial services. He is also a motivational speaker.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)